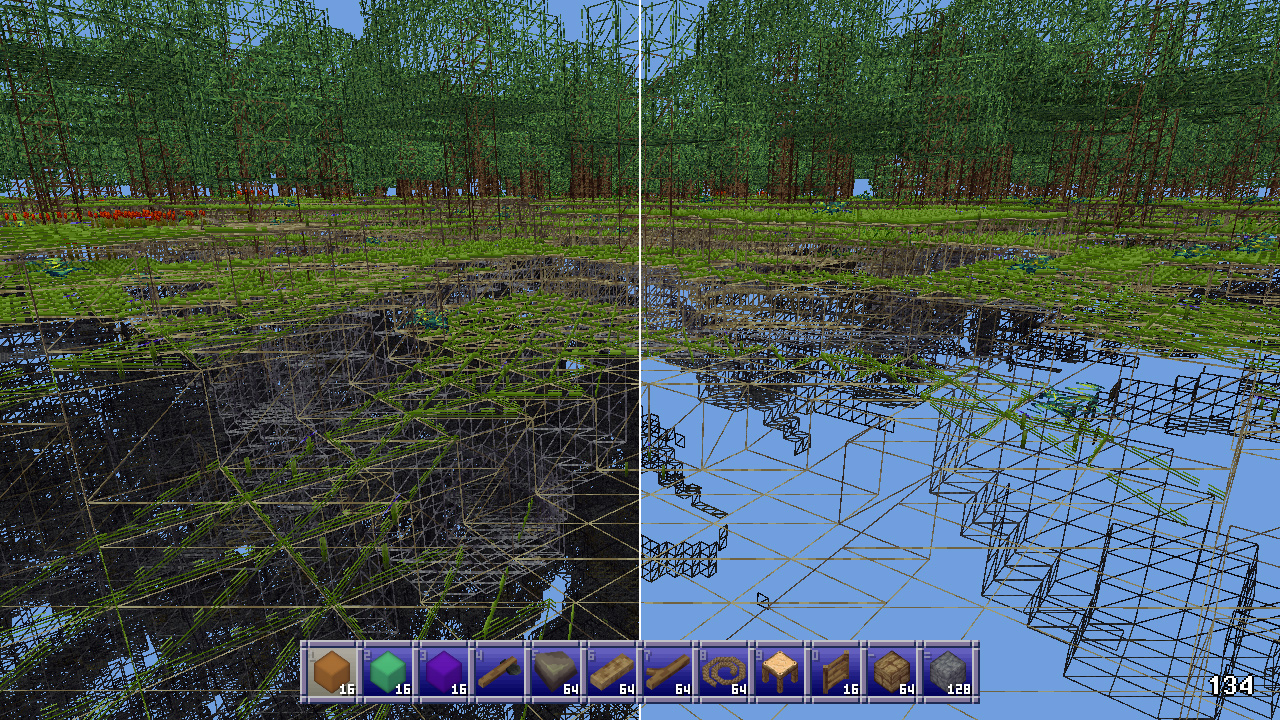

Reflective materials in Block Game

Over the holidays I implemented a system for reflective materials in Block Game. Here I’ll go over roughly how it works. I originally intended for this post to be a deep dive, but then I realized that the nitty gritty on this one just isn’t that interesting. Or at least, I’m just not that interested in doing a deep dive on it so this one will stay fairly high level.

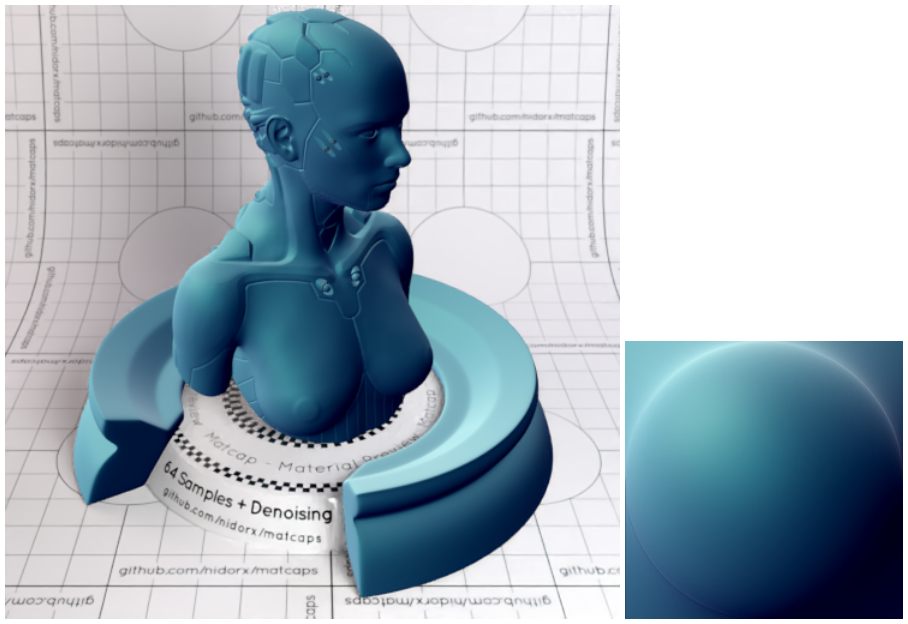

Anyway, it all started when I got introduced to matcaps over on Mastodon. Matcaps are a neat way to add texture to a model without texturing it. You obtain, via photograph, 3D render, or even freehand painting, a spherical map of a material. Then, you apply it to an object by sampling the sphere based on where the normal is pointing using the view space x and y coordinates. And that, I thought, was pretty rad.

This works because when you look at an object in view space, none of the normals will be pointing away. They’ll either be pointing sideways or nominally at the camera. So half a sphere is all you need.

And I thought to myself: hey, I’ve used the spherize filter in Photoshop to make spheres out of squares. And I also thought to myself: hey, if I flip the camera around and render the scene with a high field of view into a square texture, then I could spherize that and use it as a matcap for reflective materials!

Is this the right way to do reflective materials? Absolutely not. Does it work? Yes, sometimes very well and occasionally not so good.

Continue reading...